For the past few weeks, we've been waiting to hear if the land we're hoping to buy will support a legally permitted septic system. Mostly, this has entailed waiting around for an engineer in Vermont to make an assessment for us. In the meantime, I've been educating myself about wastewater management, trying to determine what solution will make the most sense for our non-traditional home.

The results of my research have overwhelmingly indicated that current regulations make no sense for people who are determined to be personally responsible for their role in the ecosystem where they live. At the moment, I have a distinct feeling this sort of thing is going to be a trend on our quest to build a self-sufficient life in 21st century America.

For this and the entry following, I've documented some of the things I've learned.

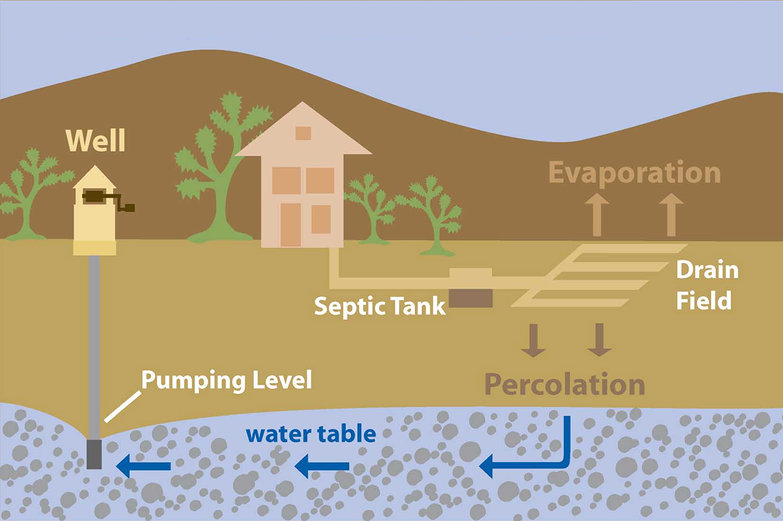

A conventional septic system has two main components, the first of which is a buried tank, usually a minimum of 1,000 gallons in size. Incoming solids (feces, food particles, clothing lint, etc) settle at the bottom of the tank, where natural bacteria break it down into a "sludge" which must be removed periodically. Until the 90s, the gunk was often pumped into the ocean or indiscriminately buried in landfills. These days, much of it is applied to commercial farm soil (after extensive treatment).

After a retention period of two or three days, the waste in the tank has separated and begun to break down. The liquid portion (called effluent) is now ready to move into the second component of a traditional septic system: the drain/leach field. Next, soil acts as a filter to remove contaminants from the effluent while it percolates into the ground. Eventually, most of the liquid seeps back into the water supply, ready to begin the process anew.

For any number of reasons, a proposed building site may not be able to support a leach field (unsuitable soil, shallow water table, etc). The most typical solution (if one is possible at all) to this problem is the construction of an artificial filter, known in the industry as a "mound system".

Essentially, this involves creating a complex sand hill to clean wastewater in the same way soil would. These over-engineered solutions require extra tanks and pumps to carefully dose effluent into the mound at timed intervals. Once wastewater reaches the substandard soil below, the liquid is (hopefully) clean enough to continue seeping into the ground water.

Frustratingly, many of the complexities inherent in these systems are unnecessary for our home. We will have composting toilets, practically negating the need to treat blackwater entirely. We will be using environmentally safe cleaners (possibly ones we make ourselves) and we will forego a garbage disposal, opting for the more sensible choice of judiciously composting any left-over food bits from cooking. Our greywater will be a resource, not waste! Honestly, the most "toxic" thing in our plumbing will probably end up being vinegar.

Sadly, in the world of self-contained septic management, conventional leach fields and mounds are the only solution with a wide precedent in our country. Somewhere on the fringes of regulatory acceptance is the option of a constructed wetland, but the stratospheric implementation costs make it moot, at least for us.

At the moment, we're following the path of least resistance: finding out if we can even install a system that regulators will readily accept (ie: a backup plan). Up next: the process and costs associated with septic design and permitting, and the response from our engineer about the viability of what we hope will one day be our land.